Football

Hell-Bent: Prior to Life at Oklahoma State, Elliott Cockrum Lived the Dream … and Then a Nightmare

Carl Elliott Cockrum’s cheekbones were too defined, and his dimples were too noticeable.

He stood in Times Square as he saw his mother, Kathleen Gray, for the first time in what seemed like forever. This was her first visit to the Big Apple, but she hadn’t seen her son in months. This wasn’t a face Gray was familiar with.

His body 30 pounds lighter and his demeanor octaves quieter, Cockrum wasn’t right, and Gray could tell.

“He was so gone,” Gray said. “Wasted. Like how a cancer patient looks. That is a mother’s worst nightmare. That your child is in New York City, in the hospital, so far away from you.”

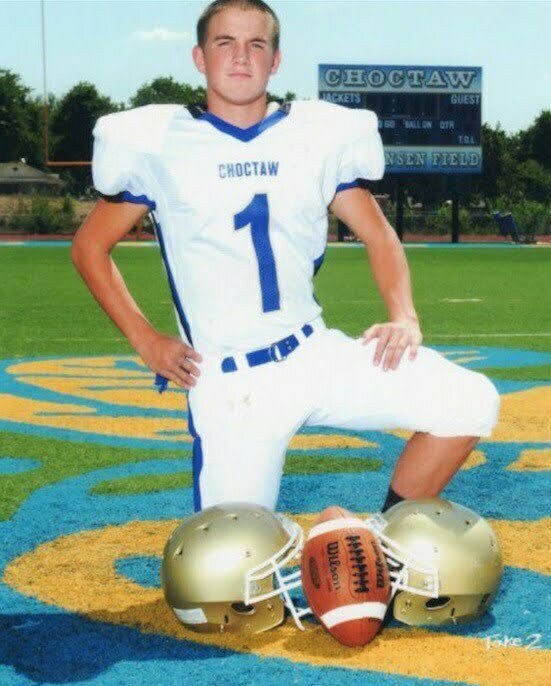

Cockrum looked nothing like he did before leaving his home of Choctaw to pursue his dreams of becoming a Division I kicker. The signs he exhibited that night in New York marked the beginning of the end of a promising kicking career, paving a path that led Cockrum to Oklahoma State University.

Kicking is as important to Cockrum as a steering wheel is to a car. He had a soccer goal at every house he lived in growing up. His parents divorced when he was in sixth grade, and his only request was to have a soccer goal wherever they moved.

The size, shape and air pressure of the ball didn’t matter to Cockrum, and he wasn’t afraid to sneak onto a high school field to practice. All he wanted to do was kick.

“In his mind, he’s always imagining a field goal somewhere,” Gray said. “He’s always lining something up. Even when you’re just talking to him, he’s halfway listening to you and halfway imagining a field goal.”

Cockrum got his first opportunity to play football when Darren Higgins, coach of the Nicoma Park Junior High football team, asked him to kick. By the time he was a junior, countless kicking camps and repetitions had Cockrum in full pursuit of his dream.

He had won a kicking camp at Oklahoma State and placed second in Oklahoma’s, validating his choice to pursue football instead of soccer.

The combination of Cockrum’s highlight tape and performance in OU’s camp led to an opportunity he thought was too good to be true.

An Oklahoma staffer, whom Cockrum preferred not be named, saw his highlight tape and called him in for a meeting, where he was told he’d receive a preferred walk-on spot with a verbal commitment.

Cockrum obliged, but the magnitude of the offer puzzled him. He knew he was good enough to kick at the DI level, but at one of the most storied and relevant programs in the nation? It seemed farfetched.

Cockrum pushed the doubts aside and shut down his recruiting January of his senior year. He stopped sending highlight tapes and prepared for his career as a Sooner.

It was August when Cockrum heard something that didn’t line up with what he was told months earlier. The Sooners contacted Cockrum and told him to try out, but they didn’t plan to take a kicker. The tryout offer felt like a courtesy, an attempt to make up for the false assurance he was given earlier.

He spent months waiting for an incredible opportunity, only to have it taken away at the last second; Cockrum had already registered for his classes. He scrambled and sent hundreds of emails containing highlight tapes, looking for another college to recruit him.

“At that point I was freaking out because I had no idea what I was going to do,” Cockrum said. “I didn’t know what to do because I had been planning this for so long.”

Eventually, Cockrum settled and spent a year at the University of Central Oklahoma, but he had to redshirt because a Texas A&M transfer won the starting job. After leaving and resuming his hunt for a spot on a D1 roster, Cockrum got direction from Scott Blanton, who trained a plethora of Big 12 kickers, including Oklahoma State’s Ben Grogan. He updated his highlight tape and sent it to every FBS school. If he knew a team needed a kicker, he would send it twice a week.

Curtis Guilliam, former offensive coordinator at Globe Institute of Technology in New York (a junior college), saw his highlight tape, gave Cockrum a call and offered a scholarship, which Cockrum accepted.

There isn’t much room for football fields in New York City, so Globe Tech practiced on Pier 40 Park, which rests on the Hudson River less than a mile from Washington Square Park. The facility was shared with soccer teams and other athletic organizations, so the Knights played their home games on Shabazz Field, which is in Newark, New Jersey.

Scouts from Akron were in attendance and saw Cockrum drill a game-tying field goal against Trinity Valley, but they never extended an offer. Rutgers became a potential suitor down the road, but the cost of tuition was a major roadblock. Little did Cockrum know, an even bigger setback was dwelling inside of him.

The start of Cockrum’s time in New York was far from ideal. He lost his wallet on his first day, and each morning started with the shriek of an alarm clock at 4 a.m.

Five times per week, Cockrum and teammates took a bus to the Staten Island Ferry, which would then take them to Pier 40 Park.

Despite the countless workouts and reps, Cockrum noticed he was losing weight as the season progressed. He didn’t have as much power in his kicks. He noticed a rash on his left side and thought it could be Staph Infection, which he had his senior year of high school. His doctor diagnosed it as a regular rash, but Cockrum continued to lose weight, dropping from 165 pounds to 157 the following week.

The symptoms continued; his blood sugar was constantly high, he needed to urinate frequently and had a lingering metallic taste in his mouth. Shortly before leaving New York, Gray asked whether everything was OK. Cockrum knew something was wrong, but he didn’t know what.

About a week after Gray boarded the plane back to Oklahoma City, Cockrum’s father, Jimmy Cockrum, landed in New York because he worked in Stamford, Connecticut, about 90 minutes away.

Like Gray, Jimmy could tell Cockrum was feeling off, so they grabbed pizza and buffalo wings as they watched the Cowboys play the Giants.

Jimmy was a type 2 diabetic, and because Cockrum figured his symptoms could be indicative of diabetes, Jimmy pulled out his blood sugar monitor and pricked Cockrum’s finger for blood. Nothing came out.

They tried again, intensifying the pricking, but still, no blood came out of Cockrum’s finger. They pricked and squeezed as hard as they could until some emerged. The results on the monitor showed no numbers, only “High” displayed on the screen.

Thinking his monitor was malfunctioning, Jimmy took Cockrum to Walgreens to get some test strips, but the results remained: “High.”

At this point, Cockrum was almost positive he had diabetes. Understanding the severity of the disease, Cockrum and his father took a trip that turned into a weeklong stay in Stamford Hospital.

After getting checked in, Cockrum learned his weight had dropped to 140 pounds. Meanwhile, Globe Tech had a game against Army Academy less than 24 hours away.

His frequent restroom visits prevented him from sleeping, and his blood sugar was an astronomical 770, a figure so high that regular monitors couldn’t read it. Cockrum finally regained a sense of normality after getting an IV and an insulin shot.

“As soon as they started dripping that fluid bag into me, I could just feel so much better,” Cockrum said. “I had forgotten … this is what it feels like to be normal.”

Cockrum calls spring of 2015 the worst time of his life. It was difficult for him to accept the abrupt ending to his season; he needed a break from football as he dealt with being diabetic, performing tasks to get his body to do things others’ bodies did automatically.

Cockrum continued to field offers from schools as he managed his health. Arkansas State said they would evaluate Cockrum if he came to their kicking camp. Cockrum knew ASU needed a kicker, so he headed to the camp in May.

He still calls it the best kicking performance he has ever had. He ran from hash to hash, kicking about 40 field goals, many of which were into the wind. He drilled a 55-yarder from the left hash, ran to retrieve the ball and nailed a 49-yarder from the right. His two misses, one from 39 yards and another from 55, still stick out to him.

Nonetheless, special teams coordinator Luke Paschall told Cockrum he could be the starter with similar performances, but he would have to sit another year because of NCAA transfer rules. J.D. Houston, a transfer from Hinds Community College, was Cockrum’s main competition.

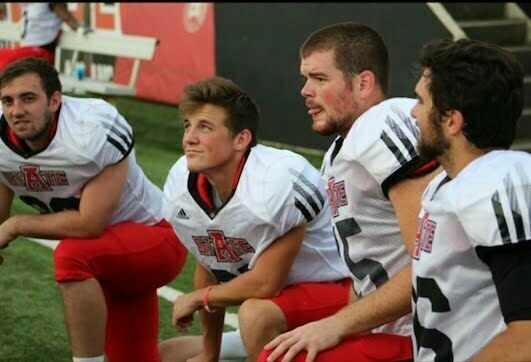

Although he didn’t play in any games his first year at ASU, he still took reps and participated in practice for the Red Wolves, who won the 2014 Sun Belt Conference title.

Sam Ellis, a former quality control coach at ASU, monitored one of the many drills during a practice before ASU’s pair of spring games. Drills akin to those depicted every football movie imaginable were scattered across the field: bear crawls, pushing sleds with 100 pounds on them, sprints, you name it.

A whistle blew, players rotated, and Ellis didn’t believe his eyes when he saw who was in front of a pack of players walking toward an agility drill.

“I’m like, ‘What the hell are you doing here, man?’” Ellis said. “I don’t think there’s any other kickers or punters or snappers that are even doing this. They’re on a different practice field, talking about girls, snapping footballs and doing their own thing.”

But there Cockrum was, competing against a safety, going one-on-one to see who could complete the drill more quickly.

“I gained a ton of respect for him when he took part in those drills,” Ellis said. “Those are drills the best athletes in the world are struggling with.

“He was Hell-bent on proving himself.”

Spring came and went, and so did Cockrum’s chances of starting for ASU. Of the three kickers competing, Cockrum made the most field goals in the spring games, but Houston retained his spot because of his successful junior season.

With one year of eligibility remaining, Cockrum could have waited another year to play, but decided to transfer and study sports media at Oklahoma State University, which better suited his academic goals.

“This is why kickers are considered flighty,” Cockrum said. “You don’t give them scholarships. A lot of kickers bounce around like journeymen.”

Even after accepting the end of his kicking career, Cockrum was one of two kickers who tried out for Oklahoma State before the 2017-18 season, but Matt Ammendola retained his spot and no kickers were taken, thus ending Cockrum’s playing career and starting the rest of his life.

Today, when Cockrum kicks, there is no time on a scoreboard. No referees signal whether the ball goes through the uprights. No opposing coach calls a timeout before the snap to ice him. He competes against himself.

“It’s just hard because I’m just now getting stronger and I’m kicking so well,” Cockrum said. “It’d be easy for me if I was getting older and weaker, but I’m so much better now than I ever was.”

Kicking has always been Cockrum’s escape, and it probably always will be. He trains just as hard now, if not harder, than he did when he was preparing for a career as a Sooner, or during his time on Pier 40 in New York City, or while competing against skill-position players in drills that aren’t applicable to kicking a football.

“I couldn’t have done it the way he’s done it,” Gray said. “I’ve never really seen him be depressed about it. I’ve just seen him always just kinda try to push harder. He’s always going.

“One thing about Elliott, is he always lands on his feet. I know that kicking will always be a part of his life. That will always be part of him.”

50,55,61 yard field goals from last nights session. pic.twitter.com/pu0xlED6vJ

— Elliott cockrum (@elliottcockrum) October 3, 2017

-

Wrestling5 days ago

Wrestling5 days agoThe Top 5 Quotes from John Smith’s Retirement News Conference

-

Wrestling3 days ago

Wrestling3 days agoOSU Wrestling: How John Smith Started a Tradition of Late-Night Workouts For Cowboys Seeking World Glory

-

Wrestling4 days ago

Wrestling4 days agoOSU Wrestling: The Impact John Smith Had on His Final Boss, Chad Weiberg

-

Hoops4 days ago

Hoops4 days agoJustin McBride Enters Transfer Portal